According to the most recent report from economic think tank Development Economics, businesses run by mothers with children aged 18 or under will generate £9.5 billion for the UK and create 217,600 jobs by 2025.

The importance of this faction of entrepreneurs stands out as their impact on the UK economy grows year on year, but the term ‘mumpreneur’ is highly contentious. It primarily refers to female entrepreneurs with children who head up businesses targeting other mums or the childcare sector. But its secondary reference is to female entrepreneurs with children in general, and that’s where it takes on a patronising meaning, according to many. The term, much like ‘olderpreneur’ suggests that women are somehow at odds with entrepreneurialism.

“I’m not a fan of the phrase ‘mumpreneur’ at all,” says Rachael Dunseath, founder and MD of Myroo Skincare, the UK’s first totally “free-from” skincare brand. “My husband is never referred to as a ‘dadpreneur’.” While she believes that running a business with a family is more challenging, with greater time and financial pressures, she doesn’t see the need to add yet another label on female founders, who are already in the minority.

New research from Barclays Bank and the Entrepreneurs Network reveals that women entrepreneurs are severely under-supported, yet tend to do a better job than their male counterparts. The results show that women-led businesses achieve far lower levels of funding, with male entrepreneurs 86 per cent more likely to be venture-capital funded, and 56 per cent more likely to secure angel investment. Female participation in business ownership is directly associated with higher credit rejection probability, which essentially means that female founded businesses are more likely overlooked and turned down for credit.

Against these odds, women entrepreneurs bring in 20 per cent more revenue with 50 per cent less money invested, according to the same study. 34 per cent of male entrepreneurs have seen a business go under compared with 23 per cent of female founders, and since 2011, investments into companies with no female directors on their board average £2.9 million, but by adding a single female board member corresponds with a typical increase of £500,000 in funding.

For many female founders, the term mumpreneur just adds to their otherness, and makes it even harder for other women with an entrepreneurial streak to take the plunge.”I’m definitely in the camp of those who feel the term mumpreneur is outdated and sexist,” says Janet Murray, a business journalist-turned entrepreneur, who runs a media consultancy from home. “I feel it demeans female business owners, as if what they are doing is a hobby rather than a serious business.”

And serious business it is. According to a 2015 study, there are 762 companies with female leadership that generate revenues of between £1 million and £250 million, and are growing by at least 20 per cent a year. This figure comes from education technology non-profit Founders4Schools, which connects classrooms with local business leaders.In total, these businesses generated £2 billion more in sales in 2015 than the year before, a figure projected to grow. According to Abbie Coleman, founder of MMB (Mothers Mean Business) and MD of Harrington Norman, the growth and influence of women in business shouldn’t be reduced to labels. “So daddy is an entrepreneur and mummy is a mumpreneur. Is that what I am supposed to tell my son? Why do I have a different title for doing the same thing? Put in that context, it really does sting and almost carries a slightly demeaning and belittling tone,” she says,

“I know there will be many who say it’s just a title, what’s the problem. But the word to me takes away the determination, hard work, blood, sweat, and tears behind my business. Why do I not deserve the same title as my male counterpart? Why does my title have to carry my status as a mother when my husband’s doesn’t?”

Launching a working parents magazine with the very aim to get more women to the boardroom through part-time and flexible working, this topic is close to Coleman’s heart. The word ‘mumpreneur’ was one she often heard, but not one she ever really understood, or took as a compliment, she says. “I started a business seven years ago, pre-children. Then I launched another business two years ago after my first child. Am I any less the entrepreneur after children I was before? Why do we need the term mumpreneur at all? It goes back to the term ‘working mum’. After all, how many dads are called working dads? Why as a women do I have to be defined in my title as a mum or a woman? Am I simply not an entrepreneur?”

But for Debbie Hulme, founder of children’s interiors brand, Kiddiewinkles, the term is only patronising if you let it define you. Hulme identifies herself as mumpreneur after founding her business in 2014, when she decided she didn’t want to be restricted to traditional working hours. Before she decided to be her own boss, Hulme was working in sales and marketing, on high profile clients included Nivea, Imperial Leather and Chicago Town Pizza.

“As soon as I became a mum for the first time, I knew that I didn’t want to be restricted to traditional working hours. I’ve always been passionate about letting children be children for as long as possible, so wanted to create a business that would inspire creative play and help parents play with their children,” she tells GrowthBusiness. “This passion led to me launching Kiddiewinkles in 2014, initially with a range of playhouses that stimulate little imaginations by offering big play potential.”

Her business is geared towards parents and children, which understandably allows her to take on the ‘mumpreneur’ label as and when she needs it.

For Brontie Ansell, founder of ethical and vegan chocolate brand, Brontie & Co, the term is more than a label, it’s a way of creating a community, and a common identity. “I identify as a mum in business,” the former lawyer says. “I think the term can be quite useful. It also lends support for those women not yet in business who think they might like to start, if they can see mums out there already doing it. I don’t think there is anything sexist or outdated in admitting that you are a mum and running a business.”

As another female entrepreneur who sees the appeal of the term, Angela Middleton CEO of MiddletonMurray, believes that her role as mum and entrepreneur are interlinked. From starting her recruitment business, to discussing various business and day to day issues around the dinner table with her daughter and son, she has always hoped that her work ethic would inspire them. Although Middleton started her business when her kids were old enough to discuss it with her, she has always taken their views on board.

But when it comes to securing funding, a top barrier to entrepreneurship, according to multiple studies, women still lag behind men, whether they’re mums or not.

A separate study by APS Financial examined what was keeping entrepreneurial women away from the start-up world. Nearly half of UK mums, according to APS Financial, say they admire businesswomen like Michelle Mone, Karren Brady and Liz Earle, but several barriers stand in their way, including it being too much of a risk, not having enough resources or know-how to get started, and the tedium of the admin involved.

Meanwhile, those who currently own a business and previously owned a business named the top challenges they faced when starting and running their own enterprise as not having enough time to do everything, the challenges of managing the business while raising children, the amount of red tape they regularly deal with as a start-up, and most crucially, finding a bank that can support them financially.

These entrepreneurs also found financial service providers as being far from flexible. Four in ten said that the process of setting up a business bank account had taken longer than expected, and nearly that number found the rates and fees were not transparent enough.

Worryingly, more than one in ten admitted they had decided to cease trading due to lengthy admin tasks such as completing tax returns, talking to their bank, and problems with keeping track of business costs and expenses.

Perceived costs of establishing a dream business were also dramatically different from the reality, indicating education about start up fees could be far better. While 36 per cent of the surveyed entrepreneurs who had started their own business had done so with an investment of less than £1,000, many of those who’d not gone into business thought their start-up would need an investment of £10,000 to £50,000 to get it up and running.

While the Barclays study revealed gaping chasm between female and male founded businesses securing venture or angel investment, this study suggests that even debt finance fails to meet female founders’ financial needs.

Equity crowdfunding is famously touted as the great financial leveller, democratising the market for both founders and investors. But the Barclays study reveals that

A similar study from Crowd for Angels has identified that just 7 per cent of its audience is female. Similarly, most crowdfunding platforms have a predominantly male audience. But according to Crowdcube co-founder, Luke Lang, women are are certainly proportionately more successful on the equity crowdfunding platform than male founders, which suggests an opportunity for female entrepreneurs working against the funding grain.

“(Female entrepreneurs) often run consumer businesses with strong brands, which could give them an advantage, and they also stand out from the male-dominated entrepreneur crowd,” says Lang.

“When it comes to creating a crowdfunding pitch, it’s possible that women might be more realistic in their targets, and more meticulous in the planning and execution, which is attractive to investors. It also takes strong communication skills to run a successful crowdfunding campaign.”

In 2015, only 8 per cent of fundraisers that picked up capital through equity-based crowdfunding platforms were women. According to Lang, women are traditionally considered to be good at building relationships and knowing how to market and promote their business, which gives them an advantage on crowdfunding platforms. ” I wouldn’t say they’re necessarily better at this than men, but what crowdfunding does perhaps is level the playing field so they’re able to fully put these skills into play,” he explains.

“Some female entrepreneurs tell us that traditional finance models can still be off-putting or impractical for women. Men are still very much in the majority in a room full of angel investors, for example, while most pitching events happen in the evening, which can be tricky if you have a family. The openness, 24/7 accessibility and lack of traditional stereotypes in crowdfunding can make it an appealing choice.”

According to Karen Kerrigan, Seedrs’ chief legal officer and director of the UK Crowdfunding Association, terms like ‘lipstick entrepreneurs’ and ‘mumpreneurs’ can skew the way investors view female founders. She wrote about her experience working with female entrepreneurs at Seedrs earlier this year on GrowthBusiness.

“We often hear from female entrepreneurs who have had this experience when attempting to raise money through traditional (mainly male) channels. Recently Vana Koutsomitis, runner up at on The Apprentice and founder of Dateplay, wrote about how she found it difficult to engage investors when her male co-founder wasn’t present. The good news is that other options are now available for female entrepreneurs to raise money, and they are taking advantage of them. Dateplay went on to raise £220,000 on Seedrs, almost double its target amount, from 359 investors – which, as Vana said, was ‘a pretty amazing vote of confidence.'”

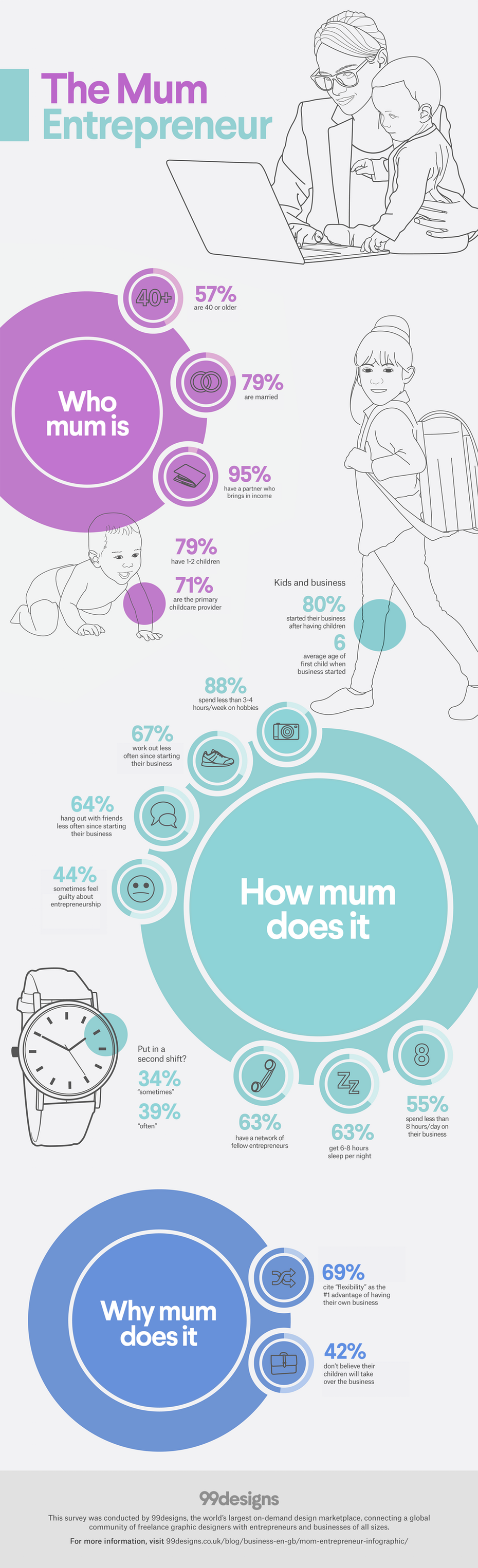

Recognising the value in unlocking this lesser known powerhouse, 99Designs surveyed over 500 mums asking them to share their successes, their fears, their lives and their advice. The quick stats are that 80 per cent started their business after having kids. 71 per cent are the primary caretaker and 39 per cent often put in a “second shift” to get their work done. Just who are these working mothers and how do they do it? Infographic below highlights some of the survey’s key findings.